Jeff Caylor, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons. Terrace farming in Vietnam.

Agricultural practices are influenced by the physical environment and climate.

People eat. It is what they do. Birds do it to. Bees do it. You get the idea.

People eat plants. Plants have the ability to transform and store the energy of the sun in the form of plant matter (mostly carbohydrates, with some proteins and fats along for the ride), some of which is usable by people and other animals. Plants store up the energy of the sun in their mass. Herbivorous animals, by definition, eat plants. They thus convert the stored energy of the sun into cows and bunny rabbits and other plant eating animals. They have to. Lacking the ability to photosynthesize the light of the sun, animals exist because they can eat plants. Some animals, of course, eat the animals that eat the plants. Humans, at least those humans who are not vegetarians, eat plants and animals.

For the first three hundred thousand years or so that humans existed, our ancestors lived off of the nuts, berries, and invertebrates that could be found in the landscape. Occasionally, they killed a larger animal and ate well for a few days until the meat turned rancid and inedible. Most hunting and gathering societies seem to have collected a lot more calories from gathering than hunting, and for those societies fortunate enough to have made their homes by the water, fishing provided an even more efficient way to add calories to the diet.

Department of Visual Studies, University of Buffalo. Sixth Century BCE, Deer Hunt from Catal Hoyuk.

But here is the thing about hunting and gathering. Both require a large investment in calories in order to eat. All living things have to maintain a balance between the calories needed to live another day—somewhere between 1500 and 2000 calories—and the calories that must be expended to acquire those calories. If a hunter expends five hundred calories running down a rabbit from which he can gain only 400 calories, he would have been better off sitting still and being hungry.

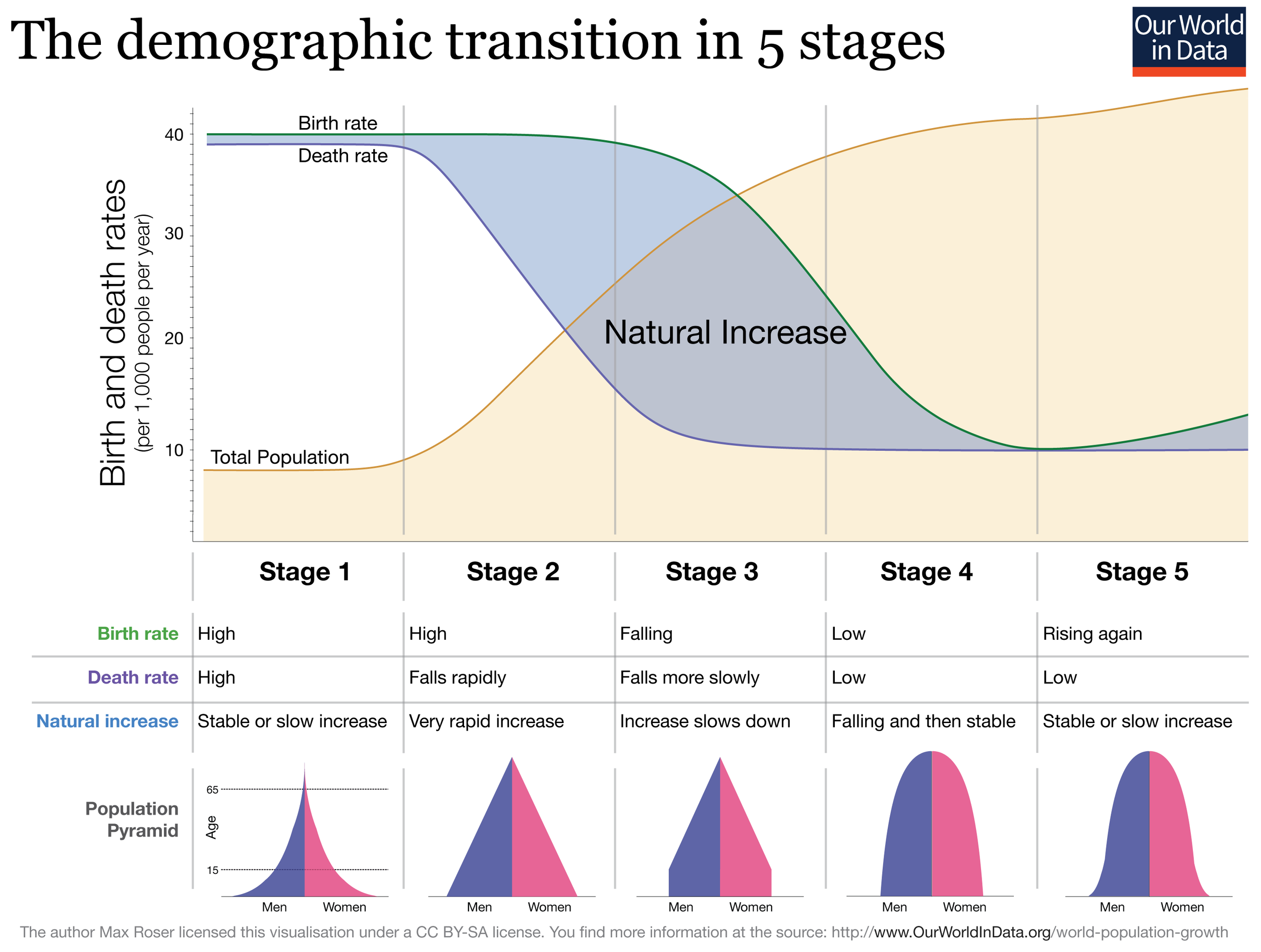

Fortunately for humanity (less so for the bunny rabbits), human hunters proved to be innovative. Projectile weapons like the javelin, atlatl, and bow and arrow allowed hunters to bring down larger, faster prey. Traps could be set for the less wary sorts of prey. Fish could be speared, netted or caught with hooks and lines. All of this allowed more calories to be brought home for the family dinner with fewer calories expended. But still, the natural world only grudgingly gives up its bounty, leaving a narrow balance between calories expended and calories gained, a reality that tended to keep populations low. High birth rates combined with high death rates caused human populations to remain stable at both local and global scales.

You might recognize this as Stage One of the Demographic Transition Model posted below. High fertility rates (meaning that women gave birth to a lot of children over the course of their lifetimes—perhaps one every two or three years between the ages of 15 and 40) were balanced by high death rates. Thus, according to the DTM shown below, a community of 1000 people would expect to see 40 births in an average year and close to the same number of deaths. Childhood mortality (before the age of five), accounted for most deaths, although young women would continue to face high levels of maternal mortality (dying in or shortly after giving birth) well into the 20th century.

But, a society living in Stage One (organized around hunting and gathering for the most part) would experience very little population change.

Stage Two represents the gradual development of agriculture, beginning around 10,000 BCE (or possibly earlier in some regions, and much later in others), which changed everything for people and their environment.

Agriculture refers to the domestication and production of plants (lets call that farming), and animals (which we can call herding or ranching). They are as different as hunting is from gathering.

Death Apple (Hippomane mancinella). When Columbus landed in the Virgin Islands, his sailors were delighted to find a “beach apple” tree with sweet, juicy fruit. So they ate it. And died. The Manchineel (endangered in Florida but common throughout the Caribbean and Central America) is among the most toxic plants in the Americas. Unwary sailors (and the occasional modern tourist), have discovered that every part of the tree has the ability to make one painfully sick and, in extreme cases, dead.

Gathering (or foraging) demands that one pay attention. The natural landscape is filled with plants that can safely and deliciously provide calories on a daily basis. Even a suburban American landscape provided dandelions, mushrooms, herbs, blackberries, and other additions to the diet that are pretty much free for the taking. The landscape (including the suburban landscape), is also filled with completely inedible plants that, while they won’t kill you, will require more energy to digest than they provide (there is a reason cows have five stomachs—they are really efficient at digesting grass. People are not). And of course, the landscape also provides plenty of plants that look like they ought to be food but that will kill the unwary forager, or at least make them very, very sick. How does one know the difference?

Our foraging ancestors (and foraging contemporaries for that matter), learned to pay attention. They gradually noticed the role that seeds played in plant propagation and, apparently, saved some of the edible seeds through the winter and planted them in the spring. When it worked, these first experiments with farming provided more food with less work than constant foraging. But this did not immediately create farmers. Modern rice, wheat, and corn do not grow in the wild. For the most part, they require human help in reproducing. Evidently, the first farmers did not just plant wild seeds, they selectively bred wild plants to produce characteristics that they found desirable. Thus, farming likely began as an extension of foraging.

Making this move from foraging toward farming was fraught with risk. Putting perfectly good seeds into the ground must have seemed like a complete waste of effort, and quite often it must have been. And some of the predecessors of our most important modern crops—like corn and wheat—were scarcely edible. The ancient ancestor of maize (what Americans call “corn”) is called teosinte. Someone, beginning about nine thousand years before the present, thought it worthwhile to plant this nearly useless grass, selecting the largest seeds, generation after generation, until modern corn began to emerge from the soil.

Teosinte, growing in Oaxaca, Mexico. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Something similar happened with the first herders and ranchers. Hunters also have to pay attention and think ahead. At some point at the end of the last ice age, it occurred to a few hunters (probably in western Asia), that there might be an advantage to protecting the wild cattle, sheep, and goats they were hunting from other predators and other human hunters. They began providing for the herds they hunted, keeping them safe and only harvesting a few animals for food and clothing. Thus did ranching begin as an extension of hunting. And just as farmers learned to produce crops with ever more desirable characteristics, ranchers killed off or castrated less desirable members of the herd—animals too aggressive for example—and created a world of domesticated animals. Along the way, people became domesticated too,.

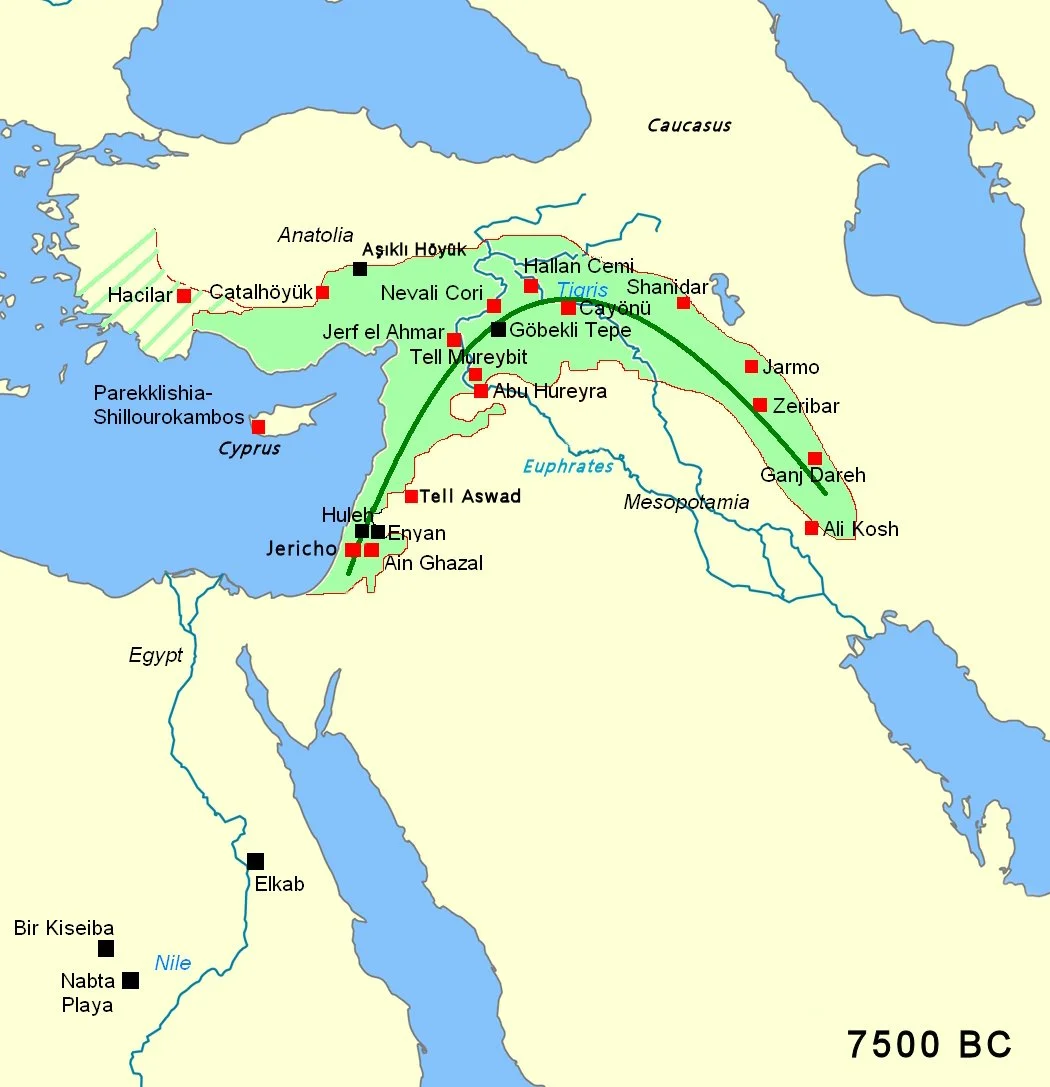

Agriculture is a complex technology. Anthropologists and historians trace the first domestication of plants and animals (and the resultant domestication of people), to a small number of agricultural hearths.

From these relatively small zones of agricultural development and domestication, technologies and practices spread widely through diffusion. As farming people moved to new regions they took their seeds, animals, and practices with them. And, as neighboring people saw the advantages of farming, they adopted similar practices. People continued to hunt and forage, and some regions were not at all suited for agriculture, but as farming came to dominate the earth’s landscape, human populations began to grow. Societies that rejected farming—or lived in regions where it was not practical—lost ground to the farmers and ranchers.

Although farming has been essential for human civilization since the first cities were built five thousand years ago, farming practices have always been exceedingly diverse.

The First Agricultural Revolution—also called the Neolithic Revolution—refers to the invention of agriculture. Although certainty is impossible, it appears that the first agricultural societies emerged in Southwest Asia—Modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel—about twelve thousand years before the present (BP). Agriculture seems to have been independently invented in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia and then, much later, in Central America. From those hearths, Agricultural practices diffused into Europe, China, India, and the rest of the Americas.

Intensive farming practices: Traditional farming practices in densely populated regions like Southeast Asia tend to be intensive. With limited land and many mouths to feed, farmers try to get as much productivity out of every square foot of land they possibly can. This often requires labor intensive practices in planting, irrigation, and harvesting. Terrace farming is an effective form of intensive farming, turning, at great cost in labor, land that would otherwise be too steep to permit plowing and planting into highly productive land.

Much of the farming one finds in the United States and Canada reflects extensive agricultural practices. Because farmland is relatively inexpensive while labor is very expensive in these countries, farmers can afford to plant fields of hundreds or thousands of acres. Tractors, harvesters, and other technologies allow the work to be done with far less labor.

But even in America, not every agricultural product can be completely mechanized. Wheat, cotton, rice, sugar cane, and much else can be planted, cultivated, and harvested mechanically, but no one has yet developed a process for harvesting strawberries, apples, peaches, or pretty much any other vegetable except by going into the fields and picking them by hand.

Photo: US Department of Labor

As an economic activity, farming can also take on a variety of forms. At a very basic level, farms are businesses—akin to factories. Untended and uncultivated, a natural landscape produces little of economic value. It takes an investment of labor and capital to turn a natural landscape into productive farmland.

Even then, there are limits as to what any given farm can produce.

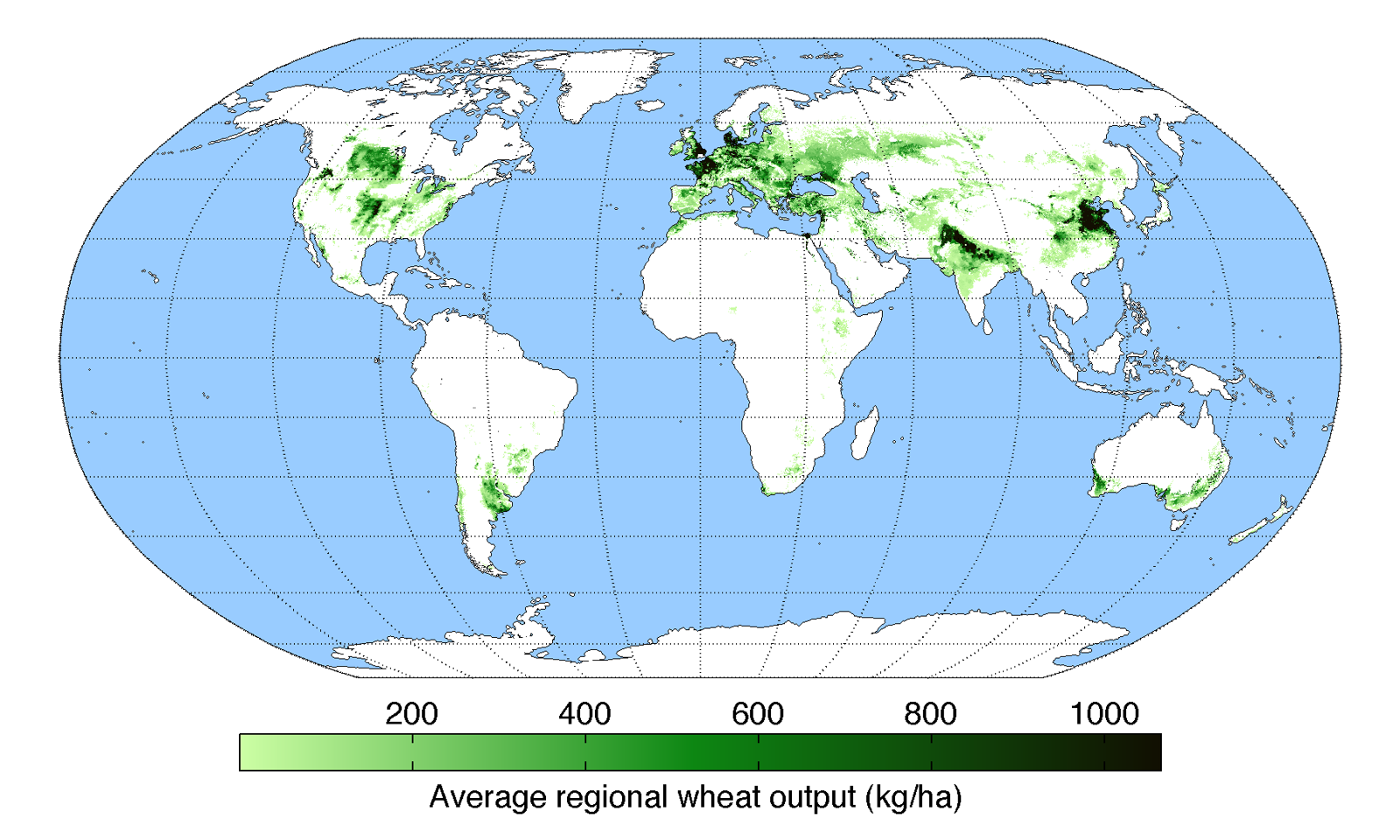

Created by Andrew MT. Average wheat production in 2000.

The choropleth world map above highlights the world’s major wheat producing regions. You might notice that wheat production, while very widespread, is limited to the world’s temperate, moderately rainy regions. Deserts produce little wheat. The tropics produce even less.

Rice production is far more limited geographically than is wheat, but is a product of intensive agriculture in South, Southeast, and East Asia. It is grown in much smaller quantities in Southern Europe and Africa. In the United States, the Mississippi Delta is home to huge rice farms, allowing the US to be an important rice exporting country in the global economy.

Most of the food consumed in the world’s most highly developed economies is produced on large, highly mechanized farms where production is focused on a single commodity. This kind of “plantation agriculture” is extensive rather than intensive, and produces commodities that can be processed, transported, and stored for long periods.

Not everything is amenable to large-scale commodity production practices. Fresh fruits and vegetables will spoil very quickly and need to be consumed (or preserved through canning, freezing, or drying) within a few days of being harvested. Called “market gardening” even when they are actually farms specialize in crops like tomatoes, strawberries, apples, and the like, are often relatively close to urban centers so that their produce can move quickly from farm to market to table. There is a reason New Jersey is called the Garden State. In the Nineteenth Century, New Jersey produced much of the fresh food consumed in New York City and Philadelphia. As railroads and highway systems, as well as refrigeration, made it possible to speed fresh fruits and vegetables to urban areas more quickly, farmers farther and farther away were able to get their food to large, and profitable, market areas.

Smaller farms also tend to be engage in mixed crop production—rotating crop production from one year to the next, raising livestock as well as crops, and thus becoming less vulnerable to market swings and crop failures. On a small scale, this is called market gardening or truck farming (“truck” because the produce is trucked directly to market and is delivered to consumers relatively unmodified from its original state.

At the smallest, most local scale, many of the world’s farmers engage in subsistence agriculture, producing all or most of the calories needed by their family with little left over to market. And, of course, many people, including this writer, devote a part of their back yard to growing fruits and vegetables, not for their economic value as much for the joy of eating produce that one has grown oneself.

Subsistence Farmers trying to sell their produce. Many of the world’s subsistence farmers are women.

Ayotomiwa 2016, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Subsistence farming often requires complex skills and time-tested practices. In places with marginal soil fertility and low population densities, farmers might shift cultivation from one place to another on a regular basis. When one field has been exhausted, it might be left fallow for several years while the farmer moves to a new field to cultivate. Some cultures practice “slash and burn” farming, burning a field to prepare it for cultivation, planting crops there for several years, and then moving on, eventually back to the field initially abandoned and starting the process over again.

Jhum Field being prepared for planting in Arunachal Pradesh, India.

Rohit Naniwadekar (2008)

And when large, grazing animals are being raised, many farmers in sparsely settled regions will move the animals and themselves from one grazing ground to another over many miles. In the American West, ranchers move sheep and cattle from one field to another to prevent them from destroying the grass crop which is essential to meat and wool production.

Rural Settlement Patterns. Before the development of agriculture, human societies tended to live nomadically. This does not imply that our ancestors simply wandered at random through the landscape, hoping for the best. While practices varied according to the climate and availability of resources, many nomadic people, both ancient and modern), followed seasonal patterns. They might set up camps along rivers and coastlines in the summer and early fall in order to fish, and then move inland to hunt during the late fall and winter.

But when they adopted farming, people began to stay put. The soil has to be laboriously prepared for planting—trees have to be cut and their stumps dragged from the field. Fences have to be built to protect the growing crops from grazing wildlife. Once this kind of work goes into a place, nobody will lightly abandon it. Cattle, goats and sheep are fairly portable, but farmland takes a hold on the people who work it.

Which means, of course, that farmers need to live close to the land they farm.

Rural settlements, the name we give to farming communities, can take a variety of forms depending on the types of agriculture practiced, the cultural traditions of the people, the presence of nearby enemies, or the landscape. The image below reflects a clustered or nucleated settlement.

Poomparai Village, India provides an extreme example of a clustered or nucleated settlement. Residents live in very close proximity to one another and make a clear boundary between the town and the farmland. Parthan, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There are other ways to organize a rural settlement. Often, settlements are strung along rivers or roads in a linear settlement pattern.

This community along Lake Champlain in Quebec reflects a linear settlement pattern. You might also notice that the farmland is divided into “long lots.” Photograph by Rene Beaudoin.

An example of a disbursed settlement pattern: Navajo Hogan and Cornfield near Holbrook, Arizona, 1889, NARA.

Land-use patterns.

Rural Survey Methods: Metes and Bounds, township and range, long lot.

Farmers lay claim to the land they farm. At the beginnings of an Agricultural Revolution (whether in Mesopotamia or China or the Valley of Mexico), we might expect that farmers lay claim to the land by the very fact of tilling and planting it and, at last, putting a fence around it. Kings and other sorts of political authorities might be so audacious as to impose a tax on the land—or, more likely, on the produce of the land—but farmers well know the boundaries of their farmland and will challenge anyone who dares move across that boundary uninvited.

The first farmers in a region might carve their farmland out of the wilderness, clearing trees in the forest, plowing the prairie, fencing in the wild places to make them tame. But soon enough, if the farming is good, that first farmer will have neighbors who will also cut trees, plow fields, and find ways to say, “This land is mine!”

Inevitable, from these claims of ownership, conflicts will arise when neighboring farmers lay claim to the same tract, the same strip of land that several farmers thought of as their own. I’ve no idea how the ancients settled these disputes though I do suspect violence was involved. But, in the modern world (at least the last 500 years or so of it), claims to own the land and the right to benefit from it by varying forms of surveying.

At its most basic, two farmers might choose a few suitably massive stones, or unusual trees, or other natural features and agree in the presence of witnesses that these landmarks separate one field from another. When the current generation of farmers dies, the land defined by those boundaries is passed on to their heirs, and so on. Eventually, such boundaries would be recorded by a government agency charged with insuring that taxes are properly paid on that property.

This traditional survey method, which makes use of natural landmarks, is referred to as “metes and bounds” and is the predominate survey method in Great Britain and its colonies, including the Thirteen North American colonies that became the United States. “Metes” refers to a straight-line measurement between two set and visible landmarks. “Bounds” refers to those visible and immovable landmarks. For example, a surveyor might begin a description at the point a particular bridge crosses a particular stream, and then follow that stream until it reaches another landmark—a stone outcropping, or even a metal stake driven into the ground. Then the surveyor would draw a straight line to another landmark or stake near the road, and then follow the road back to the bridge where the property lines meet.

Township and Range. The Metes and Bounds system of survey worked well in Great Britain and in the Thirteen Colonies, but as the United States expanded to the west, problems emerged. Careless surveyors were known to create overlapping surveys (kind of like the way shingles on a roof will overlap one another), which resulted in multiple landowners in Kentucky and Tennessee holding legal claims to the same stretch of land. Westward expansion, beginning with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 which encouraged settlement of what was to become the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota, demanded a more methodical survey system. Formally called the Public Lands Survey System (because the whole point of the Northwest Ordinance was to distribute “public” lands (a point contested by the native peoples of the region) to “American” settlers.

Because the land was largely flat and free of natural landmarks, surveyors could treat the vast stretches of the American West as if it were a massive chess board. This NASA photo of Kansas Farmland gives us an idea.

This summertime photo of Kansas farmland by NASA’s Earth Observatory shows individual fields of one quarter section each. A “section” is one square mile or 640 acres. A “township” is made up of 36 sections. The circles (and semicircles) show where center pivot irrigation is being used. The dark green circles are corn. Lighter green is millet. Brown fields were probably growing winter wheat which has recently been harvested.

Crops_Kansas image by NASA Earth Observatory. . Public Domain.

These neatly organized fields of corn, wheat, and millet reflect the “township and range” system of surveying that dominates the western landscape. While these fields have certainly been laboriously surveyed by men using transits and chains, the initial work could be done from a comfortable office far from the danger and hardship of the frontier. Settlers could lay claim to a section or quarter section sight unseen, and as long as they could plant crops, build a house, and not die, five years later the land would be theirs. Many of the farm families who grow corn and wheat on these neatly organized fields inherited their farms from ancestors who struggled with locusts, drought, and other misfortunes in order to make the land their own.

Long Lots or Ribbon Farms are rare in the United States, and usually reflect French influence as this map of the Detroit River in 1796 (and the future cities of Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan).

By George Henry Victor Collot. This is a section of an early 19th century map made under the direction of George Henry Victor Collot. Public Domain. Surprisingly, Fort Detroit, like the modern city, is on the northern banks of the Detroit River. Ontario, and the modern city of Windsor is to the south.

Long lot surveys are usually found along a river or roadway. All of the landowners in this system have access to the river. Even though the French lost Detroit to the British in 1763, their cadastral system continues to leave its imprint on the agricultural landscape.

Early Hearths of Agriculture and Domestication

Farming seems to have been invented independently in a small number of places (or hearths) from which the ideas and practices spread. The first attempts at the domestication of plants and animals seems to have begun in an area called the Fertile Crescent between ten and fifteen thousand years ago. Dogs seem to have been domesticated from wolves several thousand years earlier than that.

Plants and animals that have been “domesticated” tend to be substantially different from their wild ancestors. Dachshunds do not look much like wolves, nor does modern corn look much like teosinte. Cattle have been bred over many generations to be less ferocious than their extinct ancestor, the auroch, or the still very extant and ferocious cape buffalo of southern Africa. On the other hand, some animals—elephants come to mind—can be captured, tamed and trained, but are interchangeable with their wild cousins.

Most of the plants and animals that share the landscape with humans are not particularly amenable to domestication. Plants that provide humans neither food nor shelter are unlikely to be cultivated, at least in the early days of agricultural innovation. Herd animals tend to be domesticated more readily than solitary ones, and though dogs are descended from, and are still closely related to, wolves, most domesticated animals are herbivores. People may be unable to digest grass, but cattle, sheep, and goats can happily do so, and people have been dining off the milk and meat of these herbivores for millennia.

This means that agriculture is going to take root only where domesticable plants or animals already exist in the wild. Even today, deserts and tundra, rainforests and high mountains, are the least settled, least farmed sections of the planet.

GFDL, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons. The Fertile Crescent seems to have been the birthplace of agriculture. Plants and animals domesticated here, and the cultural innovations made possible by farming, spread from the Fertile Crescent into the Nile River Valley and Europe. It is unclear if it also influenced agriculture in the Indus River Valley to the east.

This map of agricultural hearths was developed by Nikolai Vavilov in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Even as Vavilov was creating this map, evidence of existing neolithic agriculture and communities on the island of Papua New Guinea was being discovered (in red). More recent scholarship suggests that the Mediterranean Basin (number 3 on the map) was influenced by the Fertile Crescent and was not an agricultural hearth. More recent archaeology suggests that the Eastern North American Woodlands Tribes were planting and harvesting sunflowers in the Red River Gorge region of Kentucky in the pre-Columbian era.

Chiswick Chap, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Each hearth developed around different plants and animals and different technological innovations. The Fertile Crescent and Southwest Asia gave the world wheat, barley, lentils, chickpeas, and dates, products that, about five thousand years ago, enabled the emergence of the first cities.

Southeast Asian cultures domesticated rice about seven thousand years ago. Central African cultures domesticated Millet, sorghum, yams, the oil palm and, that most necessary of agricultural products, coffee (which is also claimed by Ethiopia, but made its greatest impact on Arabia and on writers and scholars everywhere. Peruvians domesticated gourds, potatoes, chili peppers, and squash, products that spread throughout the Americas and, after 1492, throughout the world. The Valley of Mexico was the birthplace of maize (corn), and tomatoes, and that most wonderful gift of Mexico to the world, the avocado.

Patterns of agricultural diffusion. You might have noticed from this very incomplete list of plants and places that most of the culinary innovations of the ancient world continue to dominate the palate of modern consumers. This is a reflection of agricultural diffusion. Simply put, crops that are developed in one part of the world—corn in Mexico for example—tend to spread far beyond their initial home range to be adopted by cultures wherever the crop can be grown. Thus, though corn was developed in the Valley of Mexico, neighboring cultures were happy to trade for the red, blue, and yellow seeds of the maize plant and were even happier to plant and harvest them for themselves.

As cultures spread from one area to another—English, Irish, and Scots to North America for example—they brought their wheat, and oats, their apples and pears, their pigs, cattle, and horses as well. The British had received these in trade with other parts of the world, and began to adopt American products into their own culinary traditions. Thus, that most British of fast food meals, the fish and chips, was born of potatoes from Mexico and cod from the North Atlantic. This agricultural exchange involved more than agriculture and was not altogether a good thing. The most dramatic transfer of plants, animals, insects, and bacteria took place in the centuries after 1492 and are referred to as the Columbian Exchange.

The Columbian Exchange happened more or less by accident. When the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria made landfall in the Bahamas, the sailors managed somehow, to pick up a disease hitherto unknown in the Eastern Hemisphere, syphilis, one of the only diseases known to have existed in the otherwise healthful environment of the New World. The Spanish, for their part, left behind small pox, measles, and influenza, diseases which devastated the peoples and cultures of the New World.

There were happier exchanges within the Columbian Exchange. Europeans received potatoes, tomatoes, squash, maize and turkeys. The Americas received horses, cattle, pigs, sheep and goats, but also rats. The “amber waves of grain” that embodies the American, Canadian, and much of the South American landscape, were made possible by grains domesticated millennia ago in Southwest Asia.

Agricultural Revolutions have taken place multiple times in last twelve thousand years, and in the process have made other human developments possible. Cities could not have developed without farmers and the agricultural surplus their labor created. Farming allowed for the development of kingdoms and empires. Schools, businesses, exploration, war, revolution, invention and all the other stuff we learn (and teach) in history, literature, science, and math, are outcomes of the first hunter/forager to decide to raise a wolf cub as a pet or bury a handful of grain and see what would happen next.

And, a lot happened next. Historians who write about the Industrial Revolution (1750-1850, more or less) usually mention that Industrialization would have been impossible without the Second Agricultural Revolution that began in Europe in the century before the development of the spinning jenny and cotton gin. Beginning in Britain (which was also the home of the Industrial Revolution), farmers began experimenting with new crops and new methods of farming, transforming an agricultural landscape that had been largely the same since the Middle Ages. These technological changes in farming allowed more land to be brought into production more efficiently and with fewer laborers. This created untold suffering among the enslaved people of the Americas who were employed in cotton, rice, sugar, and indigo production, even as industrialization led to the unemployment and displacement of traditional farm workers, weavers, spinners and others in Britain. But just as inescapably, the clothes we wear and the food we enjoy today, as well as the leisure we take for granted, are products of these revolutionary agricultural and industrial technologies.

There is just one problem. Planet earth is plenty large, but only a fraction of it is capable of providing sustenance to humans. And, generally speaking, we do not want to live on a planet occupied entirely by humans and row after row after row of cabbages and onions, rice and beans, wheat and peanuts and chickens in cages. And since the planet is not growing, the population is. The math is inescapable (as Thomas Malthus pointed out in his 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population). Unless restrained, populations increase more rapidly than agricultural output. Until the 20th century, virtually all of that restraint came in the form of war, famine, and disease. And even though the world’s most highly developed countries tend to have zero or negative population growth, the world’s least developed countries continue to experience population growth along with poverty, disease, and suffering.

In the last half of the 20th century, Norman Borlag and the millions of agronomists and ordinary farmers he inspired launched a Green Revolution, also thought of as the Third Agricultural Revolution. Borlag argued that modern agricultural science, high-yield seeds, chemicals, and appropriate mechanization could radically increase the efficiency of farming and farm output per acre, especially in the world’s poorest countries. By and large his efforts succeeded, and Borlag has been credited with saving over one billion lives. But his success has not come without its own risks. Fertilizer and pesticides generally have to be bought from more highly developed countries, creating growing economic burdens on the least developed countries, and both pesticides and fertilizers have long-term impacts on the environment and on the ability of the land to continue producing at high levels.

Agricultural Production Regions

Subsistence Farming

Commercial Farming

Monocropping/monoculture

Bid-rent theory and the cost of land (and what could more profitably be done with the same land)

Spatial-Organization of agriculture

Large-scale commercial agriculture replacing family farms.

Complex commodity chains link production and consumption.

Economies of Scale

Global carrying capacity

von Thunen’s land use model: transportation costs, distance from market, speciality farming. concetric rings.

Food in the global supply chain

dependency on a single export or import

Main elements of global food distribution networks affected by political relationships, infrastructure, patterns of world trade

Environmental effects of agricultural land use: pollution, land cover change, desertification, soil salinization, conservation efforts.

Agricultural Practices: slash and burn, terrace farming, irrigation, deforestation, wetland loss, shifting cultivation, pastoral nomadism.

Societal effects of agriculture: changing diets, roles of women in production, economic purpose of agriculture.

Agricultural innovations: biotechnology, GMOs, aquaculture.

Sustainability, soil nd water usage, loss of biodiversity, fertilizers and pesticides

Patterns of food production and consumption: individual food choice, urban farming, community supported agriculture, organic farming, value added specialty crops, fair trade, local-food movements, dietary shifts.

Challenges of feeding a global population:

Food insecurity

food deserts

distribution inequities

adverse weather

urban sprawl and the loss of agricultural land

Location of food-processing facilities and markets.

Economies of Scale

Distribution Systems

Government policies in food production and distribution.

Women in Agriculture

Roles of women in food production and consumption.