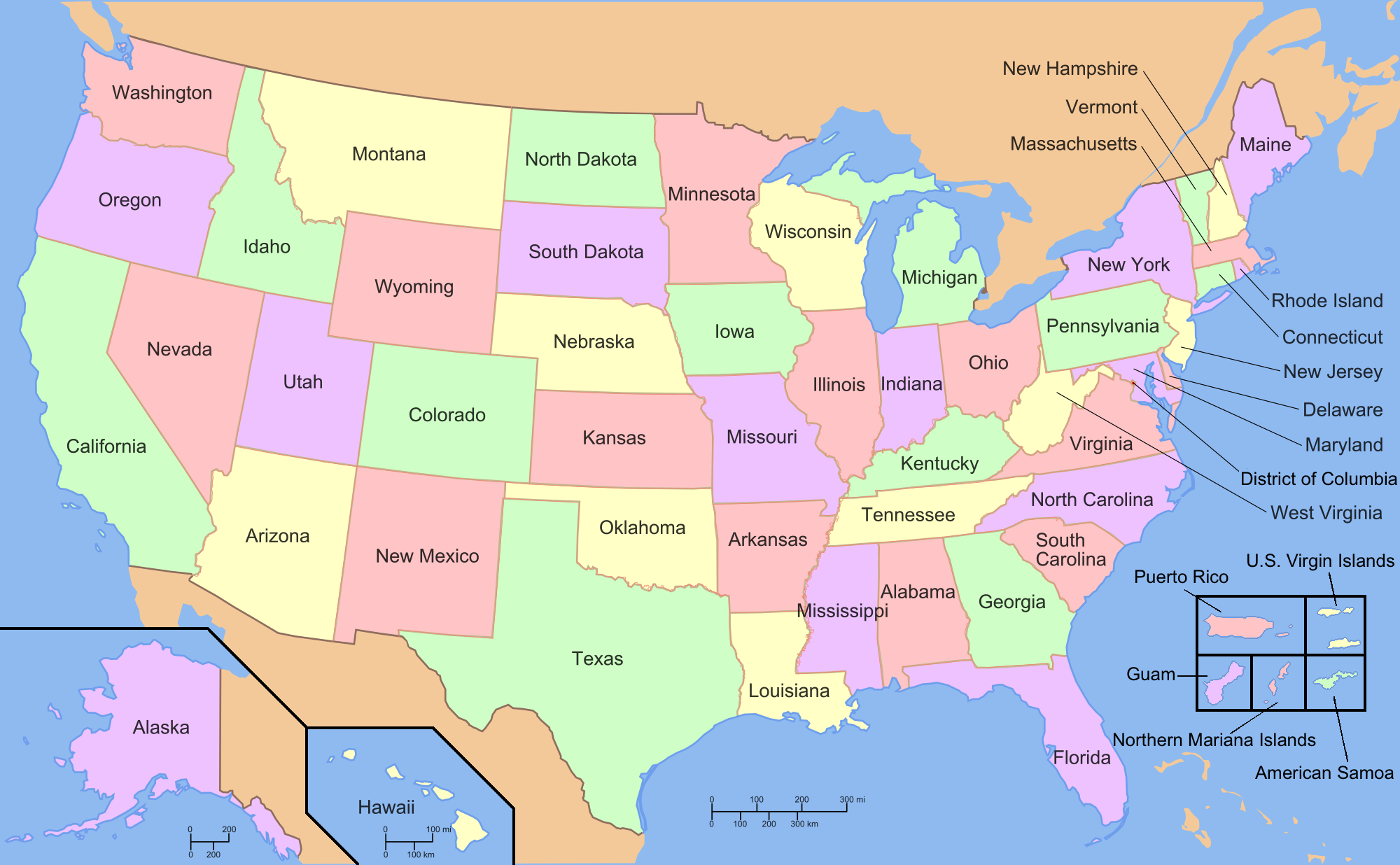

Seen from space, the United States looks nothing like this. During a flyover, the states are not labeled, nor are they color coded and it is impossible to tell where Wyoming ends and Montana begins. The long, straight boundaries that delineate parts of every state except Hawaii are invisible and completely imaginary. They were drawn on maps and agreed to by politicians who might never have set foot on the land, and drawn for reasons having nothing to do with topography, the flow of water, or the desires of the people who lived there.

But these lines matter, of course. Enormously. Drive across one state line into another and different laws apply. Different taxes are imposed. People argue about different sports teams and eat different kinds of barbecue. They go to different schools and vote in different elections. Crossing a state boundary is a big deal.

It is even a bigger deal crossing a national boundary. To leave the United States and enter Canada—one of the world’s easier border crossings outside Europe—you will need to show your passport to the American border protection officer who will look at it and wish you a good day and you will then walk or drive a few yards and show the same papers to the Canadian border protection officer who will ask you more detailed questions about the purpose of your visit and if you are bringing in any firearms or drugs, and then perhaps put a stamp on your passport and wish you a nice trip. On your return to the US, the process is reversed. Some countries make entry more difficult—they require a visa to be purchased ahead of time—and some have essentially open borders where no one looks at your passport or asks you anything at the border.

Political boundaries are completely imaginary, but they determine the rights we enjoy, the laws we follow and the taxes we pay. They reflect one of the most powerful realities of human geography during the last five centuries—the division of the planet into sovereign states. Take a close look at the political boundaries reflected on this map of north America. Greenland, a sovereign territory of Denmark, has self-evident boundaries that have not been contested since the Vikings showed up 800 years ago. The majority (88 percent) of Greenland’s 56 thousand people are Inuit and speak Greenlandic while 12 percent are Danish. Although Greenland is geologically part of North America, its cultural and political orientation is toward Europe. We would say then, that Greenland’s physical, cultural, and political boundaries are all the same.

Move to the west a few hundred miles, however and you will find a very different kind of boundary between Canada and the American state of Alaska. Most of the boundary between Alaska and the Yukon Territory of Canada runs along the 141st line of longitude. In the south, the border runs along the Elias Mountains and the Coastal Range—high mountains that make much of southern Alaska reachable only by ship or air. That long straight border represents an important international boundary, but on the ground it is completely invisible. People on both sides of the border share common languages and many cultural traits—although about twenty percent of Canadians speak French as their first language. On one side of that long, invisible border, the people people sing the “Star Spangled Banner” at baseball games; on the other side, they sing “Oh, Canada.” The long straight border represents a superimposed border. It exists only because the Canadian and United States governments (and the previous imperial governments of Russia (which claimed Alaska) and Britain (which claimed Canada) agreed to draw the lines where they did. When Alaska became part of the United States in 1867, most of this boundary had not been surveyed, and the native people who lived there were completely unconcerned and unaffected by this totally artificial boundary that had simply been superimposed onto the natural landscape. The boundary between Canada and the “lower 48” states of the United States was also negotiated between Britain and the United States in the 1840s, creating another superimposed border. Because much of the US-Canadian border is a straight line that follows lines of longitude or latitude it is also a geometric border.

The borders between the United States and both of its neighbors are undefended. There are restrictions on border crossings, but neither Canada, Mexico, nor the United States see any need to protect their borders from military attack. The countries of the European Union take this a step further by allowing open borders. Once a traveler arrives in any of the member countries of the EU, he or she can travel freely to any other country in the Union as easily as one would travel from South Carolina to Georgia. On the other hand, the boundary between North and South Korea has been a defended border since the end of the Korean War in 1953.

The Berlin Wall. Source: Noir, Creative Commons. To the left of the wall, wide death zone, patrolled by East German soldiers, separated East German citizens from the actual wall. To right, West Germans used the wall as a vast canvas for public art and graffiti.

Some borders still leave their marks on the landscape even though the political and cultural realities that created then no longer exist. The best known example of these relic boundaries is fairly recent. At the end of World War II, Berlin, which had been the German capital, was divided among the victorious powers: the British, French, Americans and Soviets. In 1961, the communist East German government began building a wall to separate the Soviet Sector (or East Berlin), from the democratic and Western oriented West Berlin. The wall went up so quickly that thousands of families were separated on different sides of the border. East German guards posted along the wall could and did shoot anyone from their side of the border who tried to cross illegally into the West. At least 140 people died attempting the crossing. About 5000 made it across safely. To everyone’s surprise, the East German government ordered its soldiers to stop guarding the wall on November 9, 1989. Almost immediately, crowds gathered on both sides of the wall. People began climbing over the wall, going back and forth, while the guards watched. Eventually people began arriving with hammers and chisels and began breaking the wall apart. In 1990, East Germany merged with West Germany and the Wall became meaningless. Its remnants can still be seen on the landscape, but it has become a relic boundary, marking a division that no longer has a cultural or political meaning. Hadrian’s Wall, which was built in 122 CE and intended to mark the northern boundaries of Roman Britain, is another, much more picturesque example of a relic boundary.

Even within sovereign states there are many administrative boundaries. In the United States, the boundaries that separate individual states are largely administrative, although the US Constitution gives certain powers to the states with which the federal government cannot easily interfere, thus giving each state limited sovereignty. Individual states, however, are criss-crossed with county lines, city lines, and administrative boundaries of all sorts. Unlike the work of state governments, decisions made by county councils, town mayors, and school boards are regulated by and can be overturned by the state government for any reason or no reason. These regions are autonomous (i.e. self-governing) only to the extent state legislatures permit. Every country has administrative districts of one sort or the other. In some countries, as in the United States and Great Britain, local administrative units are completely dependent on higher levels of government. Others enjoy varying degrees of autonomy and a few are so completely autonomous as to be virtually independent.

Making our story even more complicated, not every boundary is political. There are boundaries between cultural and religious communities whose origins are often to be found in the distant past. For example, in the year 285 CE, the Roman Emperor Diocletian divided the Empire into two major administrative districts—east and west. Diocletian was not a Christian, but the administrative boundary he established continues to the present to divide the world of the Eastern Orthodox Church from that of the Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. When, for example, a traveler crosses from Hungary, which is predominantly Catholic and Protestant, into Romania, which is predominantly Orthodox, he or she can quickly see a difference in culture as well as in church architecture, organization, and theology. Even though both countries guarantee religious freedom to all of their citizens, the historical church boundaries continue to influence both societies.

Supranationalism

Many of the issues that concern individual countries cross political boundaries and demand international cooperation to resolve. In December 2019, a hitherto unknown coronavirus began infecting people in Wuhan Province. Within weeks, it spread from Wuhan to the rest of China and then jumped to Europe and the United States. Before long, the Coronavirus Disease of 2019 (or Covid-19) became a global pandemic. A global disaster requires a global response and fortunately, most of the nations of the world had become part of supranational agencies such as the World Health Organization to deal with problems that ignored political boundaries.

The United Nations Organizations (the UN or UNO) was established in the aftermath of the Second World War to bring together all of the sovereign nations of the world into a forum where issues could be debated and addressed collectively. Other organizations that cross international boundaries to deal with special problems include the World Health Organization, the International Criminal Court, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. All of these agencies, and many others, exist because sovereign countries have seen it to be in their self-interest to work together rather than to go it alone.

Some supranational organizations are regional rather than global. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO includes the US, Canada, and most of the countries of Western Europe. It began as way to keep the Soviet Union from invading Western Europe and continues to keep its focus on regional security in Europe and North America. The World Trade Organization and the International Monetary Fund regulates international business, while the World Bank makes loans to least developed countries to help them to more effectively benefit from the global economy.